On this page

Aroids

Bananas

Bromeliads

Gingers

Palms and Cordylines

Polygonums

The science of the Jungle Score

A to Z of plants and cultivation notes

aroids

The sinister aroids

Aroids are familiar to everyone in the form of our native 'lords and ladies' or 'cookoo pint' (Arum), the 'Swiss cheese plant' (Monstera) with its wonderfully architectural leaves, and the now frequently grown 'peace plant' or 'snail flower' (Spathiphyllum). Aroids constitute a large family with many species, most of which are tropical herbaceous perennials and climbers. As one might imagine, those with tuberous or rhizomatous storage organs and the ability to become dormant in winter are somewhat tougher, and a number can be cultivated outside in most parts of Britain. Others make spectacular foliage plants used for outdoor summer decoration in tubs or large pots.

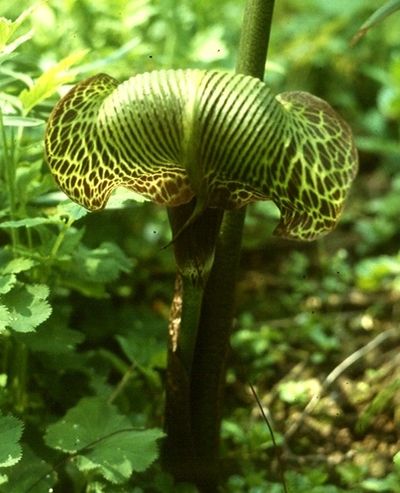

The aroid 'flower' consists of a cowl-like spathe that surrounds the rod or club-shaped spadix, at the base of which are the true, very small flowers. Many aroids employ flies of various types for pollination and one of the bi-products of this association is a tendency to have a slightly alarming odour. Tuberous aroids bear some of the most fascinating flowers of any plant group and as architectural foliage plants they are difficult to beat. Admittedly, varieties with evil-smelling flowers will not appeal to those with sensitive noses, but all will appreciate the spectacular leaves, produced either with, or after the flowers. Most parts of most aroids are poisonous.

Zantedeschias and callas

The well-known arum lilies are of variable hardiness. The toughest are those derived from, and variants of, Zantedeschia aethiopica from southern Africa. This is the familiar white arum lily with tall flower stems supporting a pure white spathe surrounding a yellow spadix. The leaves are mid to dark green and elongate heart shaped. They may reach 30 cm or more in length and are borne on 40 cm petioles from a tuberous rootstock. It is the rootstock that requires winter protection from severe frosts as in most cases, the leaves will be lost in winter. In frost free areas, growth continues throughout the year. Flowers are produced in mid spring along with a flush of new leaves. Generally arum lilies enjoy abundant moisture and Z. aethiopica can be grown in ponds as a deep marginal where the rootstock will not freeze. Plants grow best in full sun or with a little shade and produce the biggest leaves in a rich soil (JI3 with extra peat substitute in pots). The hardiest form is Z. aethiopica ‘Crowborough’ but there are some newer forms such as Z. ‘Kiwi Blush’ with pinkish flowers that are just as hardy. A little more tender but more imposing is Z. ‘Green Goddess’ which has tall flowers marked with green as though they are not sure whether they should actually be leaves. The more tender forms (calla lilies) with yellow, red, purple and pink flowers should be treated in much the same way as Canna plants with which they combine well to produce wonderful foliage and flower effects. Propagate Zantedeschia by dividing the large tuberous rootstocks in spring as growth starts. The tubers rot easily, so coat the cut surfaces in a fungicide and leave them to dry for a few days before replanting.

Aroids in pots

Most aroids are woodland plants and require a humus rich compost. Providing this is on offer, most will grow well in pots. The exceptions to this are Dracunculus and some arums which like a gritty, free-draining compost. We use JI3 soil-based compost mixed with a fibrous multipurpose composts in a ratio of two to one for most of our plants. The tuberous nature of many aroids means they can easily be repotted each year if need be, although many will thrive in the same pot for a number of years if fed with pelleted chicken manure which seems to do them good. Use a pot three to four times the diameter of the tuber. Plastic will do, but if they are to be used for summer decoration, there is no problem with terracotta or glazed pots.

Hazards with aroids

Many aroids are poisonous, often containing calcium oxalate crystals in their leaves and tubers. Even the edible eddoes (Colocasia esculenta - elephant's ears) must be thoroughly cooked to destroy the toxins.

Another risk from many aroids is the foul stench when in bloom. The woodland nature of aroids has meant that many have adopted scent as an attractive agent for pollinating insects. Unfortunately some have adopted flies and provide for them with a scent that mimics rotting fish, meat and other decaying delights. Don't cut the flowers off, just move the plant out of the way until it has completed its business.

Frequently asked questions

Q. My calla lily flowers are finished and have flopped. Should I cut them off?

A. Yes. Cut them off close to the base of the plant. You could let the fruits ripen and then try sowing the seed in moist compost in a warm place.

Want to know more about aroids?

Deni Bown has produced an excellent book on aroids. It's a good read but not laid out in a helpful way.

bananas

The banana family

The Musaceae contains two or three genera depending on classification. Musa (including Musella) and Ensete. They are doubtless some of the most impressive foliage plants that are available to gardeners and for those in tropical regions, the providers of useful edible fruits.

Planting

Bananas grow best planted in the ground where their extensive roots can gain the water and nutrients they crave. They like moist, fertile soil and should be fed with pelleted chicken manure and fish, blood and bone regularly when in growth. If grown in pots, they will need a lot of root space so as large a pot as possible should be used. Plastic pots are therefore best as they are lighter and reduce the chances of drying out although terracotta pots reduce the risk that the plant can blow over in wind. Drainage should be good since bananas do not like soggy roots, especially if the weather is cold. We use JI3 soil-based compost (mixed with a little perlite for young plants).

Banana care

One species of banana, Musa basjoo, is proven sufficiently hardy to survive with protection out of doors in much of the UK the whole year round. However it, like its more tender relatives, will fare well in a container with winter protection. Be it in the open ground or in containers, bananas are an important element in the exotic garden and cannot be exceeded for that tropical effect, with smooth, arching grey-green leaves often 2 m in length. Most bananas are dormant in winter and grow little. Some may even become leafless. With spring warmth, growth will begin. Pot on and feed if necessary, and stand out of doors as often as possible when the weather is dry and mild. Do not subject bananas in growth to temperatures of less than 5°C and avoid water collecting in the leaf bases in cold weather as this may cause rot. Ensure that they receive plenty of sunshine and plenty of water as growth begins. By late spring, it is usually safe to leave them out permanently, but watch for cool nights.

Bananas suffer from wind damage in exposed positions so stand them somewhere sheltered. Even then, leaves may split to the main vein. This does little harm to the plant, but detracts from its architectural value. More serious are snapped petioles that can result in the loss of a leaf. During the summer, expect a new leaf as frequently as every two or three weeks, and an associated increase in height of 10 to 20 cm per leaf. Tall stems may bloom, producing an arching, pendent spike with many large scales enclosing the flowers. You may even get inedible fruit! Flowered stems die, and can be cut back to the base when the leaves wither. Usually, the plant will have produced suckers and these may be left to form a clump of new stems, or severed with a sharp knife and potted up individually (provide bottom heat to help the divisions root rapidly). To keep them growing well, feed bananas frequently with a high nitrogen fertilizer and provide plenty of water. Bring under cover, all tender and pot-grown bananas before night temperatures fall in autumn to 8°C (4°C for M. basjoo) and maintain this minimum through the winter. In the open ground, remove any leaves from M. basjoo with a sharp knife at the top of the pseudostem before the first frost. Surround the plant stem with bales of straw, old carpets, or a wide drain pipe packed with straw, bracken or shredded newspaper. Cover the top of the severed stem with similar packing and cover the whole with a plastic sheet (preferably a double layer) to keep out moisture. Peg or weight down the edges to prevent wind penetration.

Banana care products

We supply various sundries for the winter protection of bananas and other tender perennials.

Frequently asked questions

Q. My banana leaves are badly torn by the wind. Should I cut them off?

A. Not unless you are really bothered about them looking untidy. The leaves naturally tear but carry on working for the plant. If the whole leaf breaks at the stem, you may have to cut the leaf off as it can interfere with the production of new leaves.

Q. I followed the instructions on caring for my banana over winter but when I unwrapped it this spring the stem has died and is mushy to the base. Has the plant died?

A. Possibly yes. Cut out as much of the mushiness as possible and try to ventilate the stump area. You may find that suckers emerge quite rapidly as the weather warms up.

Want to know more about bananas?

Bromeliads

The pineapple family

The South American pineapple family, as one might expect, is largely tropical in its requirements. Some species however, have become adapted to the colder mountain ranges of South America and are frost tolerant if kept reasonably dry during winter. Many of these will form imposing clusters of large, spiny evergreen rosettes, in conditions that suit them. The spines are often very sharp and may be hooked so should be avoided if children are an issue. Individual bromeliad rosettes die after flowering but usually produce offsets at the base at this time. The largest genus, Tillandsia contains numerous "air plants" able to survive perched without roots on any available support, taking up moisture from the air or from rain falling on their leaves. These are occasionally sold as house plants and can do well as summer occupants of the exotic garden, strapped to a piece of bark, suspended in semi-shade and sprayed regularly. Other houseplant species of bromeliad, including Aechmea and Ananus (the true pineapple) will enjoy a "summer holiday" in a semi-shaded spot.

Care of puyas and fascicularias

These are plants of more arid regions and often from high elevations in the Andes. They mix well with succulents but also work well with plants with contrasting leaves. Puyas have sharp spines along the sides of their leaves and this should be borne in mind when planting them. These plants can stand considerable cold if kept dry in winter, best achieved by covering early with a sheet of robust polythene. If you plan to grow them in pots, they do well in cool greenhouse with minimal water during the winter, but will enjoy being outside in the summer when they need plenty of sunshine and water.

Fascicularia bicolour and F. pitcairniifolia are probably the most hardy bromeliads available in Britain. Fascicularia is a little more tolerant of winter wet than puyas, but will thrive if protection from excess moisture can be provided at this time. Fascicularia forms arching rosettes of viciously spiny, dark blue-green leaves from the centre of which a small hemispherical cluster of pale blue flowers is produced. These are of little value in comparison to the bright red of the surrounding leaves at flowering. The individual flowers last for only one day, but the red leaves remain for a number of months. Plants cluster after flowering or if the main rosette is damaged by frost and will eventually form clumps up to 1 m in diameter.

As mentioned, Fascicularia requires good drainage and responds well if its roots are confined. Cultivation in containers is advised for this reason and to facilitate covering and protection in winter. Grow Fascicularia in a mixture of equal parts JI 3, peat substitute and grit. Water them well during summer and stand the container where they receive at most 2 to 3 hours of direct sunshine as they often bloom more readily in partial shade. Propagate by careful division of the clumps in spring.

Bromeliad look-alikes

Eryngium is a genus of plants that although related to carrots, bear little resemblance to these vegetables. Eryngium species naturally occur in Europe/Asia and South America. The European species are perhaps most carrot-like in that their leaves are often finely divided into spiny segments, especially on the flower stem when this appears from the basal rosette. In some species (e.g. Eryngium bourgattii and Eryngium alpinum) the leaves are blue-green with white veins. Flowers in these and the South American species are borne in clusters of teasel-like heads each with a basal ring of spiny bracts. They may be blue, purple or green in colour but it is the bracts that are usually the most showy aspect of the flower head.

It is however, the evergreen species from south America that qualify the genus as bromeliad-like in that a number of species strongly resemble some of the larger terrestrial pineapples such as Puya(q.v.). Eryngium agavifolium forms a rosette of 20 cm long, linear, bright green leaves with sharp teeth along their edges. From the centre of the rosette, a green/brown flower spike around 1 m in height is produced in mid summer. E. agavifolium is a little unusual in that it likes a moist, almost wet soil while its superficially similar relatives (Eryngium bromeliifolium, E. eburneum and E. yuccaifolium) demand better drainage. The most spectacular, but unfortunately the most problematic, of the bromeliad-like eryngiums is Eryngium pandanifolium. Forming a robust clump of thorn-edged, strap-shaped leaves, its flower spike of many small, purple heads will reach 3 m. The long leaves alone may arch to 1.5 m, the whole resembling a fierce pampas grass. Unlike the other species of Eryngium, E. pandanifolium requires some winter protection, particularly from excessive moisture.

The prickly Eryngium species (other than the exceptions noted above) require a well-drained compost and benefit from protection from winter wet. If grown in deep pots or tubs, JI 3 with extra grit is appropriate. All like plenty of sunshine so an open site is necessary. Fortunately they tolerate wind well. The European species can be propagated by division of clumps and, to some extent, by root cuttings taken in winter. The South American species are best divided in spring as growth begins.

Frequently asked questions

Q. I have seen a bromeliad growing outside in Devon. Which might this have been and is it hardy elsewhere?

A. Most likely a Billbergia, probably B. nutans. This is good to try outside and in a sheltered spot it may survive most winters. Keep a few rosettes under cover in case you lose the ones outside.

Want to know more about bromeliads?

A useful book with excellent pictures but rather lacking on outdoor cultivation in colder climates.

Gingers

Hardy gingers

There are a number of relatively hardy species of the ginger family that are quite easy to grow. The main genera are Roscoea, Cautleya and Hedychium, the latter probably the least hardy. There is one species of the ginger genus (Zingiber) that seems hardy too but Z. mioga has often invisible flowers at ground level so the gingery foliage is probably the best part.

Roscoeas (the diminutive Himalayan gingers) are of use in ground cover and in providing exotic flowers at low level. They are hardy if planted 10 cm deep in a humus-rich soil. They prefer some shade. In late spring the shoots emerge above ground and expand rapidly into a stem bearing alternate, oval, keeled leaves. Flowers are produced at the top of the stem in mid-summer. Roscoea plants die back rapidly in autumn when the remains of the foliage can be removed (check for seed capsules and save any seed for sowing in spring). Roscoea can be divided in early spring before growth begins or raised from seed sown on soil-less compost at 15 C.

The flowers of Roscoea are orchid-like in that they have a petal-like hood. Roscoea purpurea (R. procera) has purple flowers and grows around 30 cm tall. There are some excellent colour variants including a red-flowered form. R. cautleyoides is pale yellow and of similar dimensions. R. ‘Beesiana’ is taller with yellow and purple flowers.

Of the genus Cautleya, the principal species grown is the Himalayan Cautleya spicata, and that usually in the form C. spicata f. robusta. Cautleya is almost hardy and if planted with the rhizomes 10 to 15 cm down and covered with some form of protection, it should survive most winters. Ideally, it suits the base of a west-facing wall as it objects to too much sun which can scorch the large oval leaves. Cautleya is excellent in a container where it can remain from year to year, providing a good dressing of manure is supplied once or twice in the growing season. Water abundantly during growth (which starts in late spring) but withhold water during dormancy in winter when it should be kept just frost-free. Start into growth with a good watering in early spring. Cautleya is best propagated by division of the rhizomes in early spring before growth starts. Take care to minimise damage to the brittle roots and ensure that each division bears a few 'crowns' in order to establish a reasonable clump.

As mentioned C. spicata f. robusta (sometimes seen as C. robusta) is the usual form encountered. This bears maroon spikes from which emerge, in sequence, short-lived primrose yellow sage-like flowers that are orange in bud.

Hedychiums

Hedychium species vary in their requirements but are all moisture-loving ginger relatives with spikes of colourful flowers that may be strongly scented. Leaves are broad and are borne alternately up the tall stems. Hedychium densiflorum and its varieties are the hardiest and should be planted as tubers at around 15 cm depth at the base of a sunny, south-facing wall or similar situation. A mulch of straw is helpful in avoiding excessive cold. Plants in such a situation will, however, require abundant watering during growth in summer. H. gardnerianum is almost hardy and may survive in a similar situation if given ample winter protection. This species is probably better in a container that can be kept dry and frost-free during winter. This is principally because this species is less amenable to the loss of its abundant foliage that will last until replaced by the new shoots the following year. Other species such as H. coronarium and H. wardii require a little more warmth and are less likely to thrive outside. To bloom well, Hedychium species require a long growing season and are best started early in much the same way as Canna in early spring. Their growing requirements are also similar, but stand containers in a dish of water to maintain the wet soil conditions that these plants enjoy when in growth.

Frequently asked questions

Q. Are any of the hardy ginger rhizomes edible?

A. Probably not.

Palms and Cordylines

Palms - are they hardy?

Palms and palm-like plants are essential in the exotic garden. However, realistically, only a few species are hardy in any reliable manner and only one true palm is common in colder regions. A number of palms are of borderline hardiness and may spend much of the year in the garden, but should be bought under cover before frosts occur. Sadly, most palms are not suitable for outdoor exposure, even during the summer, since the atmosphere is rather dry and the nights rather cool, resulting in very slow growth.

Trachycarpus

Trachycarpus fortunei is reliably hardy throughout much of Britain with the exception of central and eastern Scotland and northeast England. Soil should be well drained, but not dry and, as with most "exotic" plants, some shelter should be given to youngsters. Trachycarpus is relatively quick-growing, all things considered, but sadly is not a particularly exciting palm. Leaves are large on mature specimens, palmate with individual leaflets separating for around one third of their length. The leaves are dark green and slightly glossy but can yellow in exposed conditions. As plants mature, the leaf bases decay into a tough enclosing mass of fibrous strands that probably assists in insulating the developing trunk. However, it is not the trunk which may require protection in extreme weather, but the soft growing shoot in the centre of the crown of leaves (the palm heart). Damage to this growing point is usually fatal since, like most palms, Trachycarpus is unable to branch or sucker. Trachycarpus can reach considerable size, particularly in sheltered sites. On mature plants, large sprays of flowers may develop from yellow sheaths. In warm years, small black fruits may be produced.

Only Trachycarpus fortunii is grown extensively and is widely available as young plants. Other forms with a similar natural distribution may prove hardy, such as T. wagnerianus with smaller, pleated leaves and T. nanus, a dwarf palm. Grow all Trachycarpus in sun or partial shade and provide ample water in summer when they are at maximum growth rate.

Cordylines

Two species of these woody-stemmed rosette plants are suitable for the tropical-style garden, indeed the resilience and relatively fast growth rate of Cordyline australis probably makes it one of the most widely grown exotics. From New Zealand, Cordyline australis has long green narrow leaves that reach nearly 1 m in length on vigorous plants. The leaves are unarmed but the tips are sharply pointed. Each mature rosette consists of up to 100 tightly spiralled leaves that are gradually shed from the base as new ones form. Eventually, plants will produce large hanging clusters of hundreds of tiny cream-coloured flowers with a pleasing scent. The flowers may be followed by small white berries. After flowering, the stems usually branch and in time, these plants can develop numerous rosettes at a height of around 3 m or more. There are now numerous cultivated forms of C. australis with red, pink, purple or yellow leaf markings. Some of these are the result of hybridisation with C. indivisa. Hybrids (which include most of the purple-leaved forms) usually have broader leaves than forms of C. australis and are less hardy so if you plan to grow Cordyline in a cold area, make sure you choose the species or a variety with narrow leaves. Of the coloured forms of C. australis, ‘Coffee Cream’ has coppery purple, rather long leaves and is tough survivor. ‘Torbay Dazzler’ is an old form with pinkish midribs and yellow leaf margins. A healthy plant of this form is a truly shocking sight and so plants should be sited with care for it will otherwise steal the show. Cordyline indivisa (also from New Zealand) is a bolder, slower-growing Cordyline with leaves that reach up to 2 m and are as much as 10 cm in width on vigorous plants. It is less hardy than C. australis but is otherwise similar in form.

Grow species and varieties of Cordyline in fertile, well-drained soil in a moderately sunny or partly-shaded site. If growing them in tubs, use a fertile, soil-based mix with a little extra peat substitute and feed frequently. In winter, protect the crowns of young plants with plastic sheeting in order to prevent water collecting among the bases of the young leaves where, if it freezes, it may kill the growing point. Stems that have lost their growing point usually die, but suckers are commonly produced at the base of such stems. These may be left to grow again or can be removed, once they have around 15 leaves and a few cm of stem, and encouraged to root to form new plants. Variegated plants may suffer from blotching of the leaves in wet winter weather.

Frequently asked questions

Q. I use a black bin bag over the crown of my Cordyline to protect it from winter wet. Does it matter that it is not transparent?

A. Not really. Your plant will be dormant and growing very little. If you use a bunjee to hold the bag on, it can easily be removed and replaced as need be.

Want to know more about palms

This is an expensive but luxurious book on palms. It includes cycads which are not really palms but look a little like them.

Polygonums

Polygonum or Persicaria?

Persicaria is currently the accepted name for most of the plants formerly included in the genus Polygonum. However, many growers use the names interchangeably. We think of polygonums in the broader sense including Fallopia, Reynoutria and Fagopyrum. All have heads of small, bell-shaped flowers in reds, pinks and whites but their real interest to the tropical style gardener lies in their foliage.

Outstanding foliage

For the tropical style garden, polygonums (mostly persicarias) are very useful. They range from giants like Persicaria alpina to tiny carpeters like Persicaria capitata. Probably the commonest is Persicaria amplexicaule which comes in many varieties, most of which have reddish pink flower spikes on longs stems above the foliage. There are some coloured leaf variants which are valuable for variation. Persicaria microcephala has a number of coloured leaf form including 'Red Dragon' and 'Silver Dragon' which are must -have jungle plants. Persicaria runcinata 'Purple Fantasy' is also really good but slightly invasive. These are all reasonably hardy plants whereas Persicaria odorata (Vietnamese coriander) is a proper tropical but really useful to grow in a pot for its foliage and culinary use. The foliage of most polygonums is frost-sensitive and will look a mess in the late autumn. Clear them away as soon as this happens. If your polygonums get frosted in spring, they will usually throw up new shoots within a matter of weeks.

Problems with polygonums

Reynoutria japonica (Japanese knotweed) is a highly invasive notifiable weed in the UK and is notoriously difficult to eradicate. Nobody should have to suffer this in their gardens. But wait, stand back, imagine what the plant hunters who bought this back from its native eastern Asia must have seen in it for it forms wonderful thickets of exotic bamboo-like stems clothed in large tropical leaves. Truly a wonderful discovery! Giant knotweed (Fallopia sachalinensis) is bigger, more impressive in every way, and just as problematic. The two hybridise! Fallopia baldschuanica is also invasive, but often upward. The Russian vine can rapidly smother its support and a lot more. All of these plants should not be given garden room and we stock none of them.

Frequently asked questions

Q. Persicaria alpina looks a little like Japanese knotweed. Is it as invasive?

A. No, it is very well behaved and spreads only slowly. Safe to plant but remember to support it as it tends to get top-heavy.

Want to know more about polygonums?

Can someone please write a book about these fantastic plants. In the meantime...

The science of the jungle score

Leaf physiognomy

Leaves can tell us a lot about the environment in which they develop. The way leaves have evolved similar features in similar environments has been studied by many botanists. The adjacent text shows some of the factors on which our Jungle Score system has been based. If you would like to explore this subject further, please click on the illustration to the right.

Talks and lectures

Alan is happy to offer public lectures and talks on this subject and many other aspects of botany and geoecology. Please contact us if you would like further information.

Example topics -

The origin and evolution of flowers

Pollen and pollination syndromes

Plants and soils in a changing climate

Bananas: origin, evolution, breeding and cultivation

The evolution and diversity of the Araceae (arum family)

Mon | Closed | |

Tue | Closed | |

Wed | Closed | |

Thu | 14:00 – 17:00 | |

Fri | Closed | |

Sat | 14:00 – 17:00 | |

Sun | 10:00 – 16:00 |